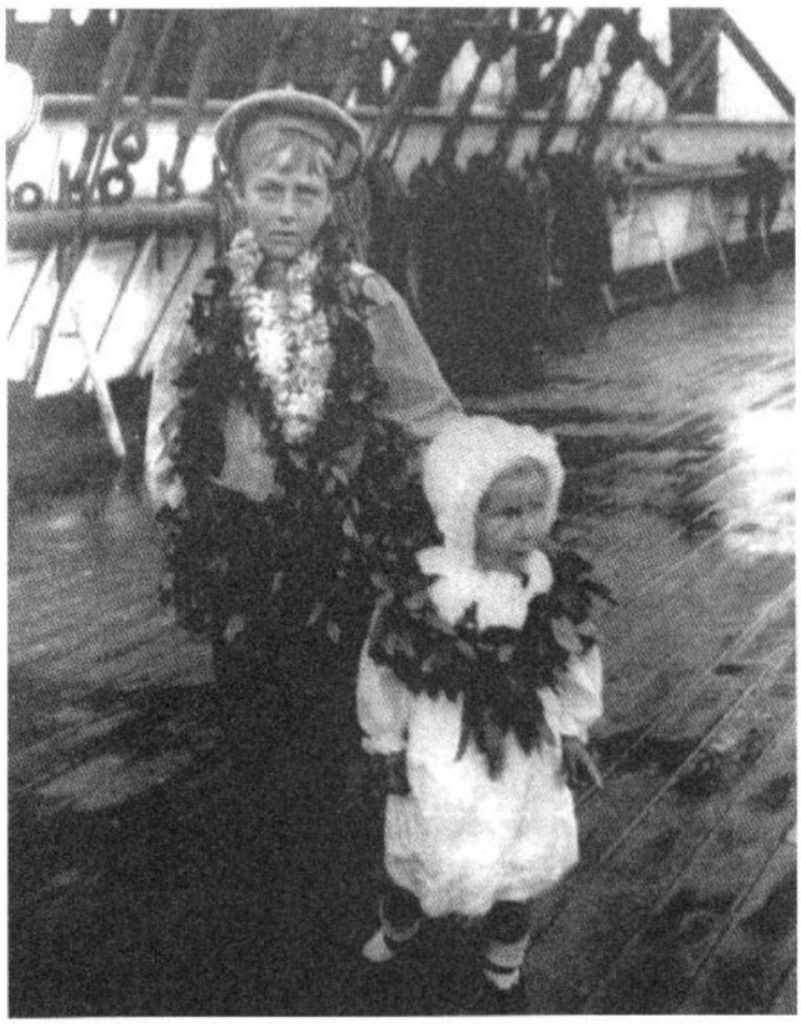

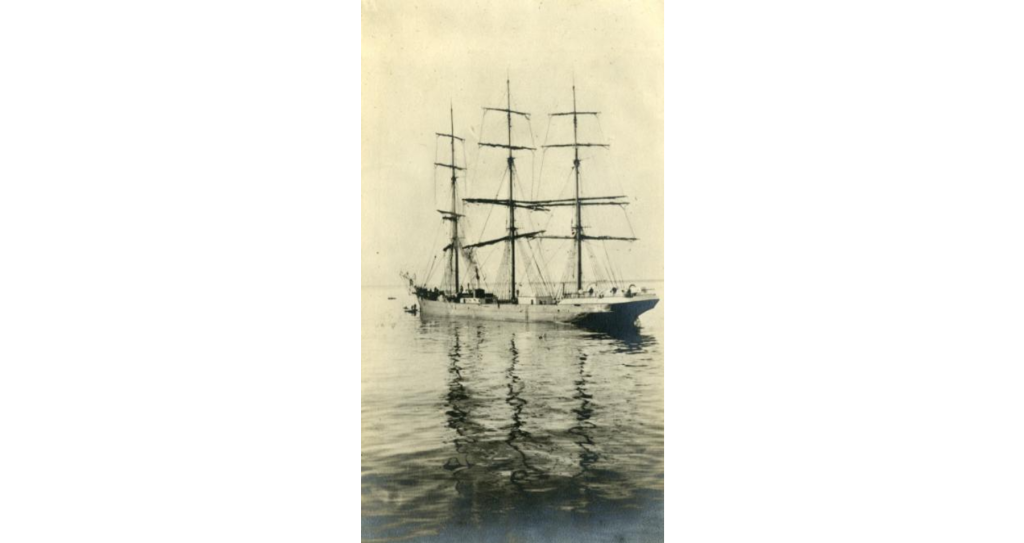

Today, Weeden & Co. is a venture and start-up management firm. We look for opportunities at the intersection of finance and technology. We will only invest in companies where we can leverage our knowledge and relationships to build successful and seaworthy ships in the tradition of the S. S. Marion Chilcott.

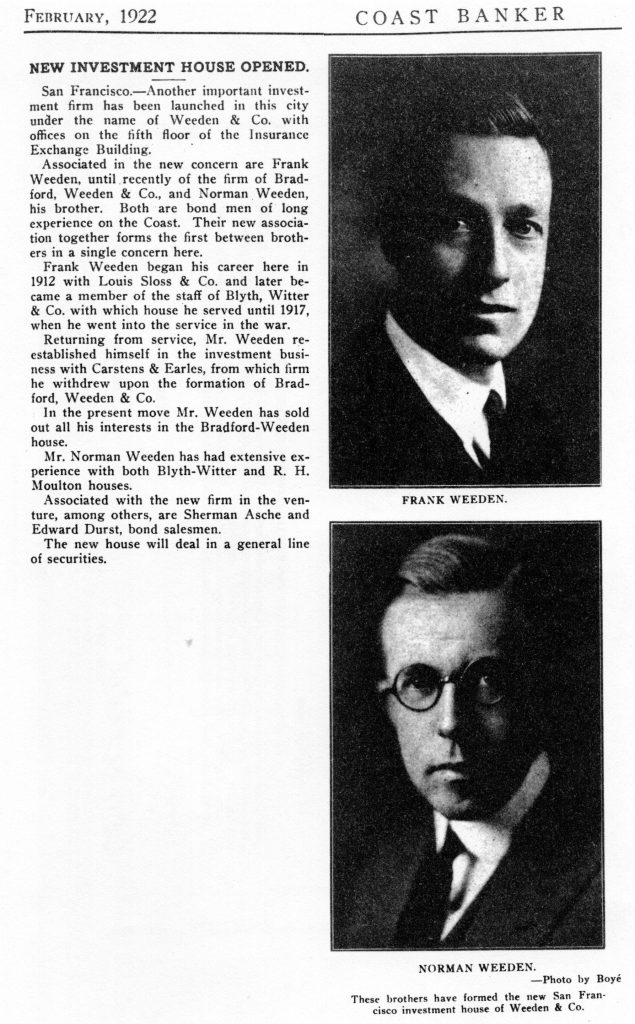

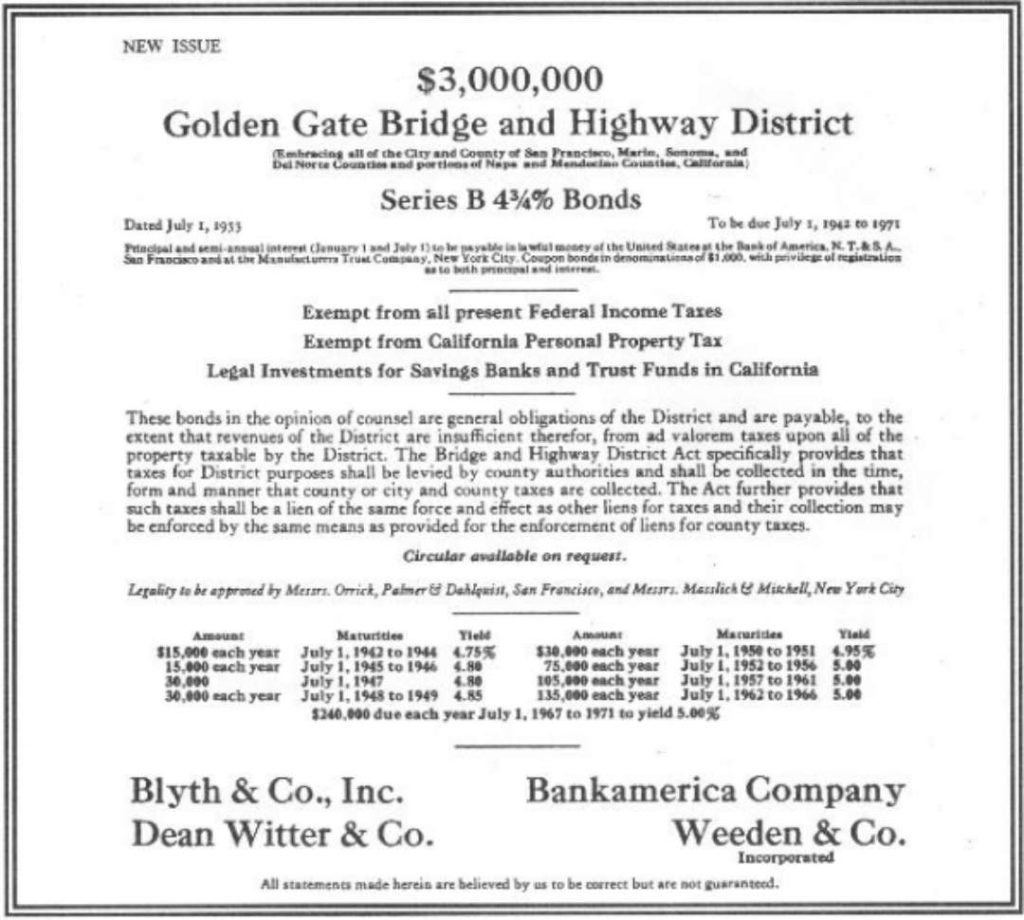

After working at the San Francisco firm of Blyth, Witter, Frank and his brother Norman started Weeden & Co. with a $20,000 loan from their father, Captain Henry Weeden, in 1922. (Of historical interest, Blyth, Witter split up in 1924. Charles Blyth started another firm, Blyth Eastman Dillon. This firm was purchased by PaineWebber, which, in turn, was purchased by UBS. Meanwhile, Dean Witter started his eponymous firm, which grew to become the largest retail firm on the West Coast. Sears purchased Dean Witter, but was later sold to Morgan Stanley. The roots of these firms continue to this day.)

Before starting Weeden, Frank often went on sales calls with Dean Witter. They pitched bonds to small banks in Oregon and Washington during the day, but at night, they would stay in their business suits and frequent the rough lumberjack bars of the northwest. The two would sit quietly at the bar until they became too tempting a target. Eventually, a lumberjack would approach and taunt these two apparent stiffs. One thing would lead to another, tables would clear, and Dean and the lumberjack would face off. Frank’s job was to make and collect bets. Dean would then remove his jacket, roll up his sleeves, and assume his posture when he was a collegiate boxing champion. Their nightly winnings were often more than their daily bond commissions.

On one occasion, Dean Witter said he couldn’t meet with a small bank and told Frank to make the sales call independently. Dean told Frank, “Don’t worry if you don’t sell any bonds, as the client is one tough and ornery customer.” Frank took the ferry to Marin Co. and walked into the bank with a briefcase of bonds. “I’m sure, sir, you know much more about these bonds than I do. Please take a look to see if anything might interest you.” The customer scrutinizes Frank, the bonds, and comments, “Young man, I am so tired of young, arrogant salesmen telling me what I should buy that I truly appreciate your attitude.” The ornery customer buys the entire briefcase of bonds, and Dean is stunned when Frank hands him a very large check.

Frank and Norman ran Weeden on a shoestring with nary a white shoe to be found. Weeden & Co. was profitable from the onset and stayed so through the Great Depression.

For instance, Frank had to rush bonds to a client. He handed the messenger a one-way fare. The messenger asked Frank for the return fare, to which Frank replied, “Sorry, there’s only an urgency to deliver these bonds.”

Frank ran Weeden, but it was managed more as an understanding than by discipline. At one point, one of the traders began to drink at lunch, and Frank needed to act. Frank asked the trader to join him for a walk around the block. But Frank could not bring himself to fire him, and they kept circling the block. The trader, realizing the reason for the walk and Frank’s clear unease, appreciated what became a second chance. He never drank again during trading hours.

The financial industry’s structure was important to Frank, who became involved in committees after the Great Depression. In September 1937, Frank joined the Investment Bankers Code Committee. Frank and the committee decided on guidelines that focused on standards and principles rather than details. For instance, they recommended that the institution’s capacity be disclosed to the customer while placing an order – whether as an agent or principal. Frank spoke for the committee:

“In the last analysis, we are going to be judged and regulated according to whether or not we serve a proper function. I am inclined to think that in the past about the only excuse for many houses being in business was the fact that they were making a profit. Now we are being analyzed not alone by the Securities and Exchange Commission but by the public at large and the politicians in Washington as to whether we perform a necessary function.”

The Investment Bankers Code Committee also recommended that the industry self-regulate. From this committee emerged the National Association of Security Dealers (“NASD”), which regulated the firms that were not members of the NYSE. NASD eventually becomes FINRA.

In 1967, Alan, Jack, and Don Weeden, Frank’s sons, staged an intrafamilial mutiny. They presented to the Weeden Board the ultimatum that either Frank step down as president or the troika would leave the firm. They believed Frank’s frugality and old-style management style restricted the firm’s growth during the frothy late ’60s. Alan became president, Don took control of stock trading, and Jack ran the back office.

Events from 1967 to 1978 are well documented in Don’s book, Weeden & Co. The New York Stock Exchange and the Struggle Over a National Securities Market (available here) and a lead Institutional Investor article called The Tragedy of Don Weeden, June 1978. During the decade between 1967 and 1977, the new management grew staff, greatly increased overhead, made two acquisitions (Wainwright Securities was purchased for $3M and written off after five months), and fought the NYSE on negotiated commissions and market structure.

In 1974, I started at Weeden to program a system called the Automated System for Trading (AST). Frank always called it a half-AST system, but AST was, in fact, Frank’s baby. AST brought efficiency to Weeden’s trading operations, which was thoroughly embraced by the old tar. Operators on the trading desks entered trades directly into the system, and inventories, profits, and risks were immediately updated. The AST was the first real-time inventory management system on Wall Street and greatly interested many major trading firms. Our software team was led by Jeremy Connelly, a great first boss who would interrupt a meeting on complex software design to declaim on Swann’s Way.

Though a rookie, I got to work directly with Frank, who, without management responsibilities, focused his energies on the AST system. Frank endlessly came up with features to improve the efficiency of trading and sales. We developed software to provide real-time bid/ ask prices for bonds, a monitoring system alerting sales teams of trading opportunities, and real-time trade confirmations in each office. While working to integrate AST with Quotron, Frank was offered the opportunity to purchase a large block of Quotron stock, resulting in Frank becoming Quotron’s largest shareholder.

During these years, Don and Jack were very active in defending the Third Market from the New York Stock Exchange, which considered the upstairs or Third Market in competition with the floor. The industry had continual discussions about market structure, and the SEC established the National Market Advisory Board (“NMAB”) in 1975 to explore the advantages of different platforms. Don was a big proponent of an industry-wide CLOB (Central Limit Order Book), allowing an open order book and a level trading playing field. To prove the viability of such a system, Don and Jack decided to reassign the AST team to build a system called WHAM (Weeden Holding Automated Market). Frank complained bitterly as he knew that Weeden’s survival depended more on trading efficiencies than convincing the industry to change.

As losses hit Weeden, Don took over in 1977, but by then, Weeden had gone through most of its accumulated capital and had net a capital deficit. Don fought hard to cut personnel and offices, but revenues dropped faster than costs. Unqualified, I was promoted to Vice President of IT one morning and told to lay off five keypunch operators by afternoon. Weeden was now, sadly, a sinking ship. Amid the flotsam and jetsam, I negotiated the giveaway of the WHAM system to Peter Madoff, Bernie’s younger brother. Don, in a final desperate effort, asked Frank to provide sufficient capital to keep the firm afloat, but Frank deferred, preferring to retain his significant stakes in Quotron, Instinet, and other investments.

Weeden was forced into a merger with Moseley, Hallgarten, at which point Frank purchased the AST system and set up QV Trading Systems. As an independent company, QV signed up trading firms such as Nomura, Wertheim, PaineWebber, Smith NewCourt, UBS, Drexel Burnham, and even the New York Stock Exchange. Frank passed away in 1984, and most of QV’s ownership passed into the Frank Weeden Foundation, run by Alan Weeden. I then left QV to start Document Technologies (“dTech”) to develop software for the SEC’s new EDGAR system. Our software, EDGAREase, quickly became the leading software tool for filing electronic financial documents.